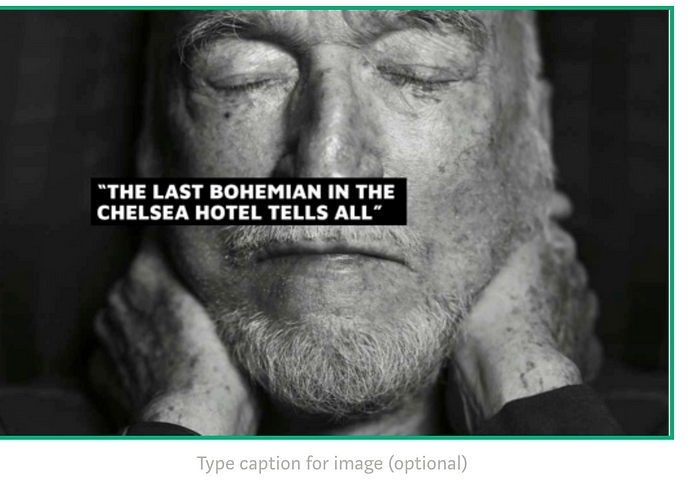

The Last Bohemian in the Chelsea Hotel

(based on the feature documentary by the same name, Directed by Jessica Robinson) www.themanonthefifthfloor.com

I was born in Abilene, Texas, on December 16, 1935, at the very peek of the Dustbowl, one of two of the most disastrous events in the 20th century in this country: the Depression and the Dustbowl, which happened at the same time. There were no trees, no grass, nothing, the winds had turned it all into a hard desert. Dust was everywhere — it was surreal.

I was the last child of four, I had two brothers who were 17 and 18 years older than I. My parents had a small store, they sold clothes, salt, anything people would buy. They lost it, they lost everything in the Depression. And the Dustbowl wiped everybody out.

They were prairie people, from another world. They never tried to work through or resolve their things but held on to those stories and to that stress for the rest of their lives. They never got over being angry, they could not forget it or forgive it. Their whole life was configured by that emotional intensity.

My father and mother were both the last of eleven children in their families and they were very religious, Southern Baptists. They would construe the Dustbowl as something biblical. Reality for them was belief, and what they believed was real. Period. Whatever happened was like a medieval play. It was God speaking to them and telling them about evil. They tried to rationalize it in religious terms.

But the irony is: existence is not rational, it is absolutely outrageous, crazy and absurd and by trying to simplify and rationalize it and you make it more absurd. Religious belief runs rough-shot over rationality.

When I was two, we moved east. I grew up in Tyler, Texas about 400 miles from where I was born.

My mother had musical talent. But her retreat from reality after the Depression was to become an invalid. She had chronic arthritis. When I was a child, my father disappeared, and I became her caretaker. Later on I would even carry her places. If she got angry with me she would tell me that I was God’s punishment to her. I never saw her smile.

I knew fairly early that the whole religious thing was made of a lot of her fantasies because all the so-called positive things like love were not present. It was all about suffering and judgments and making other people raw. She was terrible.

My parents did not talk about anything factually, including my homosexuality. It was kind of acknowledged, but there was a dictum: if you did not call something by its real name then it was alright. If you did call it by its real name it suddenly took on a different nature. Words were holy. Like in the Bible: in the beginning there was God. They took it very literally, they watched every word, they were careful not to name anything. Because if they named it, there would be an intimacy with evil.

Every night before we went to bed we had devotional readings from the Bible, followed by a commentary from the Baptist Standard, a publication in the Southern Baptist Convention. “They have such good things to say about the scriptures,” my mother would comment with sincerity. “Of course, the Bible needs no explanation. If you just read it every day, you’ll know the right thing to do.” During those pre-bedtime devotionals, I was frequently reminded to thank God, on my knees, for my many blessings.

In those days, I was fervently religious, I even wore a J.I.M. button, the letters JIM in red on a blue background. One day, as I was leaving my English class, my teacher noticed it on my shirt collar and asked: What does JIM mean?” Embarrassed, but emboldened, as I’d been instructed to be, and which was the purpose of wearing the JIM button, I blurted out: “Jesus Is Mine!”

My consciousness at that time was heavily influenced by being a gay boy. Hiding it became my major aim.

I slept in the same room as my parents until I was about seventeen. So my sex life, in general, was what you can get away with under the cover, literally. Masturbation as a little boy — you don’t even know that you are doing it, at first. Playing with yourself when your parents are a few feet away.

It was sex that turned me on. It wasn’t really people! It was sex itself, the pure physical thing: the ultimate pleasurable escape from reality. Sleeping with my parents in the same room, anything I could do to relieve that tension.

As my particular brand of sex was prohibited. I developed a kind of imperviousness to being condemned, or scolded, because I was constantly finding ways to covertly do all this stuff. It was kind of being a criminal. You know, how can you do this and get away with it?

My ticket away from depression and despair was really my talent. We had a Sears Roebuck piano at home, a very old one, you could order it from their catalog. It was made of rosewood, and it was huge and heavy. It was not a very good piano, but it worked. And it had real ivory, which is all yellow even in white. My sister was a singer and I accompanied her. She didn’t have much talent but she was the prettiest one in the family. She was a closet lesbian: You don’t call it by its real name. That allows you to do it. As soon as you name it, it restricts you.

When I was about five or six I started playing the piano at church. They had services all during the week and during Sundays, maybe 8 or 10 services, and I played for them all. The piano was my escape. I could not get away from my parents, I depended on them. I had to be there. But I could I could distract their judgments about me morally by being very flashy at the piano, and make them forget. I could escape the boredom by being a performer, and I loved the attention, so I really laid it on. And I was very good at it. I was a child piano prodigy.

Chapter Two- Piano Lessons

The town I grew up in ⎯ Tyler, Texas ⎯ had a strange phenomenon of very good piano teachers. Almost all of them were women, all were married and all went to our church. I was especially lucky when I was fifteen years old and met a man who came from Bern, Switzerland and had taught piano at Ithaca College in New York State. His name was Oscar Ziegler. He was to become the most pivotal person in my life.

Dear Oscar ⎯ a sweet, rotund man in his mid 60’s when I met him. He was very good-natured and fun, and he was the first man I ever knew who wrote poetry. He would read Heinrich Heine from a book with a silk cord, and cry. He had bought an Asian Ambassador, the first fiberglass car ever made, and he drove through the country to say goodbye to his friends before returning to Switzerland.

He happened to come to Tyler to visit a rich lady I knew, Ms. Virginia Sutton. She had taken a liking to me when I was 13 when she had heard my first piano solo recital in the Educational Building of the First Baptist Church. So Ms. Sutton invited me over to play her brand new Steinway Model M baby grand piano for Mr. Ziegler. I chose Chopin’s Scherzo in C sharp Minor, my flashiest piece ⎯ it worked. Mr. Ziegler decided to stay in Tyler and become my teacher.

He took a job at the junior college but I went to his studio. Oscar was so diplomatic, he had all the charm, poise, and elegance of a European: bon jour, merci. He ‘got” my mother, who was very weary of anybody who was not Baptist ⎯he knew how to handle her perfectly.

There was an old-fashioned, big Southern sheriff who belonged to my church and he kept insinuating that Oskar Ziegler was gay. ‘A homosexual’, he said. He wasn’t at all, but they needed someone to go after.

Oskar gave me copies of the New Yorker. That was actually when I knew, as a child, that I was coming to New York to live. There was no question.

Oscar Ziegler changed my life.

Just 6 months after I had begun working with him I won a local competition and appeared as the soloist with the East Texas Regional Symphony Orchestra, playing the first movement of Beethoven’s piano concerto #3 in C Minor.

There were two black colleges in Tyler. The people who taught there were from Julliard ⎯ they went from Julliard to Tyler, Texas, in the 1940s ⎯ good God! It was still very prejudiced and mean and nasty. I became friendly with these teachers, they were smart and funny. My father took me aside and said: “Son, we don’t socialize with niggers.” But I felt like an outsider myself, and I was getting a lot of attention for my musical abilities from them. They came to hear me play.

I used to play in black churches. It was permitted. Because of the formality of the occasion there was no danger of contamination. To be seen with a black person outside church though — that was really bad. Sunday was their only day off, and they spent the whole day in church. They ate there, they sang all day. I only came to perform and could not hang around for too long.

The music was based on 19th century hymns. The harmonies were very simple and the organist played them like they were written, but I would fill in between, like a jazz improvisation. They frequently gave me a spot on Sunday night services, doing a solo, which would be a variation on some familiar hymns.

In high school I discovered that Jesus was probably a black Bedouin Jew. I would love telling all that — it made them crazy!

Catholics and Jews and blacks, you did not associate with them. You would buy from them, you’d take piano lessons from them. My mother would even make fun about other Baptist churches. There was always discrimination and exclusivity in these small worlds. All social life was religious life, a form of tribalism — all fundamentalism still comes out of tribalism: making other people wrong, identifying enemies. Buddha was the first to say: You will never be satisfied by making someone else wrong, because then you depend on them.

In those days, Mexicans were a level below blacks, they were like cockroaches. They picked corn for a quarter a day. But there was a Mexican Evangelist named Angel Martinez, a onetime shoeshine boy turned traveling Baptist revival preacher who, to his credit, transcended all that: he was charismatic, very handsome and charming, he had the perfect theatrical sense and knew exactly how to dress. Angel Martinez could have easily been a lawyer. He had memorized a great deal of the Bible ⎯ the King James version ⎯ and he would recite it perfectly.

During the summer, big churches would hire an Evangelist to come for two weeks to preach every night at Bible meetings. It was the old 19th century idea of Revivalism.

Angel Martinez came to Tyler with his son and his chorus director, who was an army trumpet player. I played the piano. He loved my playing and invited me to travel with him.

We were at a football stadium and there were 3000 farmers and their wives, they were there with their Bibles, and he won them over. “If we can get the woman to cry by playing music,” he said, “her husband will give money.” I never quite understood that. I was 15 years old. It was my first job, $100 a week: that was like a million dollars. I bought flashy clothes. It was fabulous. We once traveled to Rusk, Texas, about 25 miles from Tyler, for a performance at a Bible meeting, and I fell madly in love with a young minister. I stayed with him. And I used to sleep with him in the same bed. But there was never any love making. I am sure he was gay too … but he kept his hands to himself. I am sure he was gay too.

One summer, Angel Martinez decided that my spirituality was lacking because I asked too many questions, and he fired me.

My mother’s ambition for me had been that I’d become the organist in our church. But I knew that I had to get away from her, to get away from Jesus, and Texas.

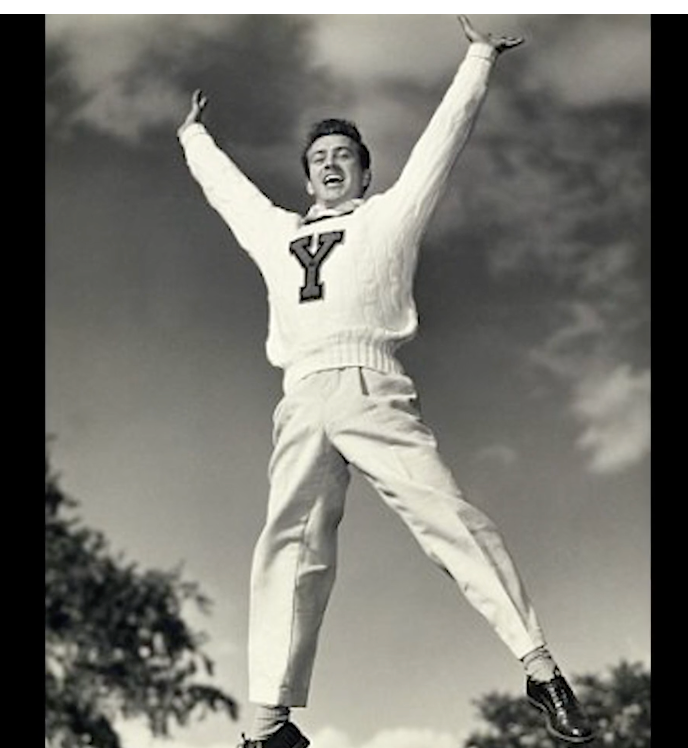

CHAPTER 3- YALE

I made the decision to go to Yale in the summer of 1958. I had not even applied, I just wrote them a letter and said I was coming.

I knew that in the preceding winters they decide who’s coming for the nextyear…and so, they wrote me and said: you can come up but you are not guaranteed you will get in.

I borrowed some money and took the bus to New Haven. 56 hours. Non-stop.

I went to the music school…and said, “I’m here.” They said:” who are you?”

Well, they said, there is no place for you, but take the entrance exam anyway, then we’ll see again if anybody drops out but now we have no place for you… so, I took the entrance exam and made 98 on it. I remember the person who graded the paper wrote: WELL!

It was exciting and thrilling to be around such incredibly smart people,

but I always felt like I was just a visitor, I was just tapping into this. I didn’t feel like I’d gotten home, that I’d found myself.

I had a single room, which was fairly rare. And next door to me was a

guy named Austin Toll. He lifted weights and was kind of kooky. He

majored in physics.

He knew about my being gay, I had told him. And he said: “Watch out

for me when I bring girls up and I’ll watch out for you when you bring

up boys.” He was charming and sweet, yes: he was wonderful.

My piano teacher had been a pupil of Theodore Leschetitzky. He was

one of the strangest human beings I have ever known. He was old and kind of wizened and something had happened to his hands. He

could still play the piano but his fingers looked like great blocks of

wood. He would rush over to you and take your hands off the

keyboard and close the lid down and say “That will be all for now.”

There were two prizes that were offered for piano players, I won

those, and I was kind of bored. I kept studying piano but I never

played a recital, because you always play a recital when you’re

finishing your music degree, that’s the big thing.

It was around that time, without realizing it, that I started thinking

about becoming a composer. I used to go into the basement of

Woolsey Hall, a huge rococo auditorium. It’s a wonderful place. The

practice rooms for the music school were located in the basement

and up at the top, which were also places where people had sex.

They installed two new practice organs built by a Dutch company

called Holtkamp. I loved organs, I grew up with them so I would

sometimes break into these rooms, just to improvise. One day the

curator of organs at Yale knocked on the door and said “Hello Mr.

Busby, is that Messiaen?” and I said “No, I’m improvising” and he

said “In that case you’ll have to leave.”

There was a club — I can’t even remember the name but it wasn’t Skull

and Bones and it wasn’t about money and business connections. It

was kind of an archaistic thing and I felt honored when they invited

me to one of their meetings. They all bunked with girlfriends and

fucked them, and then they talked about the schedule of doing the

laundry. That’s all they talked about. Then it came to me. Now I’ll

have to tell them “Could I bring my boyfriend and do the laundry too?”

But I decided I would not make that confrontation. I was very

disappointed because I had wanted to be a member of that club.

I had these short romances with some graduate students, we’d have

sex once or twice and I’d fall in love with them. They would

disappear, they didn’t want to be boyfriends.

In 1958 there was a witch-hunt, which happened every now and then,

and people suspected of being homosexual were called into the

campus police office and questioned. Of course it was very nerve

wracking.

You were supposed to deny it: If they asked if you were a

homosexual, say no. And if you named somebody else you thought

was homosexual they’d let you off.

That was the procedure.

It was a don’t ask-don’t tell atmosphere. Still, it was nasty. Anyway, I realized that it was an opportunity to tell the truth. I don’t know why I did it because it was traumatic, but I said, “Yes, I am.

And I’m not telling you anybody’s name.” So they said “The only wayyou can remain a student is to see a psychiatrist every week and admit that this is a disease.”

The one guy who stood by me was a protégé of Alfred NorthWhitehead’s. His name was Nathaniel Lawrence. I’d taken his course on Whitehead and his philosophy of religion. When I went into his office, he said: “Well, what is it, did you steal or are you homosexual”? I said “homosexual,” and he said “Well, ok.”

In my second year at Yale I chose German as my foreign language,partly so I could write to Oscar Ziegler and thank him for all he’d done for me. I worked long and hard on that letter. It wasn’t easy to write.

The very day that I finished the letter I got word that he had died. Iwas so lost, and so depressed. I’d missed my chance to say “thank

you.”

In addition to German I took a course in existentialism, which was

fairly new then at Yale. It excited me, and I thought “this is more fun

than practicing the piano.”

I decided I would major in philosophy. So I transferred out of the

music school and into the college, which was an unusual thing to do.

It was a huge social change too because instead of living in rooms

around the campus and going to this kind of trade school, suddenly I

was ensconced in Branford college.

Some of the first courses I took in philosophy were about religion

because I was still edging myself rationally away from being a

Baptist.

And then I read Kierkegaard, and the most precious, ineffable things in my life were suddenly articulated. Here at last was my bridge away from religion.

I had to have a good reason why I wasn’t loving Jesus, why I wasn’t going to church. I had to find reasons. And the irony of that was, of course, that reason in itself isn’t that important. It’s all about the commitment.

Kierkegaard constructed something similar in saying that there were stages. The first stage is the aesthetic mode of existence, when you come to terms with the way you feel and see. And then it moves if you move, and you move it to the ethical where the aesthetic is put to test, and the tests are kind of interesting and varied. His book oh, I adored that! He would edit his things by reciting them and walking. I loved the rhythm of the sentences and the syntax, it was all about walking. The rhythm was intrinsic to all of this.

I graduated in 1960 with a BA in philosophy.

* In 1973 the American Psychiatric Association declassified homosexuality as mental disorder.

Chapter Four: On The Road

I reached a point where in my head, I was going to be a concert pianist. Realistically, that wasn’t happening. When I graduated from Yale, I came to New York and took a job in advertising and then in publishing as a textbook salesman. I had never thought of myself as a composer. It didn’t dawn on me. When I started working for Random House and Alfred Knopf as a traveling salesman, right when Kennedy was assassinated, I had a Steinway grand, I sold that. I gave away all my books, my library, some records, LP’s and so forth and took this job as a college textbook salesman. It was an escape. It was my Kerouac, On the Road period. I left everything behind, my hopes of being a pianist, my being a philosopher, anything academic that I had dreamed about I just abandoned and went off. It was an amazing experience. It was incredibly depressing at first to be alone so much. Then I began to love it

Every day after visiting a college teacher for whom I had a textbook, I would go to the music school practice rooms and find a piano and play for two or three hours. I did this every day that I was on the road. I could almost always find one. If I couldn’t find one in the music school, I would find a church. Most big churches had a piano. I’d go through the bathroom. I’d raise the bathroom door and step into the toilet. I’d do anything to find a piano. I almost always did.

That was my life. It was a vagabond makeshift, do-as-best-as-you-can-with-what-you’ve-got life.

One day in a practice room in Colorado I wrote down a piece on manuscript paper, something I’d been improvising. It was like an epiphany. Suddenly everything was different. I played it back. I made a connection between the written notes and my emotion. The piece, I remember thinking, it can’t be any longer than I can remember because I don’t write anything down, whatever that means. An enormous change took place when I suddenly had this short little piece written down. I knew instantly this was it. It was, yes. It sounded good and there was an excitement. There was a knowledge that had nothing to do with books or with anything other than … I remember thinking it was like having been walking and walking and walking without knowing where I was going and then suddenly I was there.

. I took a job, the same kind of job with Oxford University Press. I had New York as my territory.

CHAPTER FIVE — GAY SEX IN THE CITY

So I moved to New York. The gay sexual revolution had happened.

This was opposite of my strict Baptist, repressed upbringing and homophobic years at Yale. It was outrageous. I remember walking into a restroom at Christopher Street, at Sheridan Square and the room was full of naked boys — all doing it.

The subway johns were just hotbeds. It was wild! And your wildest fantasies could be realized just for that few steps.

There had been warehouses on those docks at the end of Christopher Street, from about Canal Street up. And there were these huge frame structures that had been abandoned because the ships no unloaded there. I think the ships all went to New Jersey and Brooklyn.

So there were all of these trucks lined up against these warehouses, these small warehouses. They were empty and they were all facing out, right next to each other. And they would be full of gay men having sex.

It was a strange and surreal atmosphere.

It was a cafeteria. Organism wasn’t really the point. The point was the excitement and the adventure and dressing up to see who you could attract. You put yourself on the block and wait to see who bids on you.

That’s when I was doing my cowboy number. I didn’t do a leather number, that didn’t appeal to me — it was too much trouble. It was kind of expensive and I didn’t look particularly good in it anyway. So I did what I had grown up with which was 501 Levi jeans and a cowboy hat.

And that became my persona

I thought I was very hot.

Chapter 5 –Paul Taylor, RUNES

My very first commission was predicted by a psychic.

??????guest star with the Royal Ballet and so forth when they would come to the Met in the summer. We went backstage. I met Nureyev and I met his partner, Wallace Potts. We became friends. Wallace knew Paul Taylor. Wallace told Paul about my music. Paul Taylor commissioned me to write a piece. I got my first commission from Paul Taylor that way.

That all happened through those channels, that’s how that worked. It was not until Paul Taylor suddenly asked me to go with him and his company. They were spending the summer, six weeks, at Lake Placid. There’s an enclave of where widows of oil executives go in the summer. There was this big room. I had been there with Martha Graham. I worked as a rehearsal pianist for her. Paul would just say, “Watch rehearsals and pick out a dancer or two that you like very much and write a piece for them.” I did. Then he would proceed and say, “Now we need a slower piece,” now da-dum-da-dum-da-dum. That was how it came out. Again, I would improvise these pieces. I’d write them down but they all came out of improvisation. I would work late at night in a library on a funny old grand piano. I would record my pieces on reel-to reel-tape and then give it to him. Each piece was two to three minutes long. He would choreograph it and then slowly start arranging it in an order, forming a suite of twenty-two minutes, with seven movements. At the end of that time he had asked me for- and I’d agreed to do — a small orchestral piece. I really didn’t know how to orchestrate. I just said, sure I’ll do that, not knowing how in the world I was going to do it. Runes premiered in Paris at the old Sarah Bernhardt Theater right across from the Chatelet on the Seine. Its New York premiere was at a theater at 50th and Broadway. I’ve forgotten its name. It was one of the old theaters that was taken over by some religious group. Now it’s back as a theater. Anyway, we ran for three weeks there and I invited Virgil to come. He sat in about the third row. I was in the pit playing the piano. At one very quiet passage in a piece, I heard him say rather loudly, “This isn’t boring.”

Chapter 6: 3 Women

A friend of mine sent a tape of my music to Robert Altman’s publicist. When Altman had finished shooting one film he would start writing the script for the next film. Anyway, he had just finished shooting 3 Women. He had a studio in Westwood near UCLA. Everybody would gather in his office, the editors and all of his people. His buddies in those days were Lily Tomlin, Peter Boyle and Elliot Gould with whom he was making films. He gathered them into his office and said “I want you to hear some music.” He had three tapes, he had his audio engineer play my tape and two other composer’s. Altman took a stopwatch

and timed how much silence elapsed before anybody spoke, how engaged they were. Very Zen. it had nothing to do with explanation or knowledge or anything else. It was just pure engagement. The one who had the longest silence won. It was mine.

He called me and said “I like your music.”

I was cooking in a restaurant on Columbus Avenue called Ruskay’s, I was peeling carrots when the phone rang. It was Robert Altman. I could hardly imagine this, but that’s how that happened.

He asked : “have you ever written a film score?” I said no. “Have you ever conducted an orchestra?” NO. “Can you?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Okay the job’s yours.” That was one of the most astonishing things in my life, that shot in the dark, how he knew.

He operated entirely by instincts, by intuition. He was all antenna. Sometimes he’d make crazy mistakes. He would really trust if he had a feeling about something or somebody. He would go for it a hundred percent knowing well it might be horrible. He invested total confidence in me. That was amazingly transforming. That was, I think, the most transforming relationship I ever had with any other person, to be with somebody of that brilliance and magnanimity who totally trusted me for no reason. He didn’t know what I was going to do. It was the most excited I’d ever been in my life.

I had about six weeks to write it. I would wake up often in the middle of the night sweating thinking when is he going to discover I don’t know what I’m doing and send me home. It somehow came. I wrote the first piece and he said, “That’s wonderful. Just write music wherever you want.”

He introduced me to John Williams who at the time was working on Close Encounters of the Third Kind and had written two or three scores for Altman. John Williams found me the players, people who could read quickly and played modern music. We went to Burbank to one of these incredible movie recording studios that has everything in the world in it. All these musicians came in. I said, “You’re all highly recommended by John Williams. I’m delighted to have you. I have to tell you that I’m not a conductor.

They looked like oh dear, what are we in for, but they got it. I said, “This is chamber music……

demanding and very larger than life and weird. That had a lot to do with it, too. Somehow it was creating this arena of emotion and fate and the inexorability of life of moving in directions and doing things to you over which you have no control and actually no knowledge whatsoever. I didn’t think like that. This all came afterwards. It was all visual. For me, the easiest way to write music is to pictures and to words.

It’s like something that already has a sequence, it already has a rhythm. The music creates a context within which this rhythm is hopefully amplified. Altman taught me an interesting thing in that regard. He said that when movie music succeeds, the listener in the audience in the theater literally confuses the music with his own emotion. He thinks he’s feeling it and not hearing it.

Chapter 7: A Wedding and Falling in Love

Altman, as a reward, gave me an acting job in his next film called A Wedding which was about two families, a hick family, in which Carol Burnett was the matron and Paul Dooley the husband, Mia Farrow was in it, and a rich family, Dina Merrill and Vittorio Gassman and they were coming together. There was a part for a Baptist minister. I overheard Altman talking about the character of the Minister, what he was saying wasn’t true about Baptists; how they look and how they behave. I corrected them: No, Baptists don’t wear collars. They don’t wear crosses. They don’t talk like that. Altman said, “Why don’t you play that part.”

So he asked me to be in “A Wedding” because I had grown up as a Southern Baptist and there was a role for a Southern Baptist preacher. So I rewrote the script and did my own thing.

We were filming in Waukegan, Illinois, which is north of Chicago.

There were mansions that extended from Chicago north along the lake that had been very fancy in the early part of the 20th Century. Rich people lived there. And then slowly this area had kind of come down and some of these were starting to fall apart.

The one we were shooting in had had this big conservatory where they had kept plants, but all the glass was broken and everything was kind of a wreck, and he used that as part of the film.

The spirit of the film was that these families were broken and kind of crazy and yet they were pretending to be very elegant and the environment was beautiful.

And there was the lake, that was the reason the families were driven away, it was getting closer and closer to the houses. That’s where we shot.

I’d spend weekends in Chicago which was not far away and I went to the big gay bar downtown called the Gold Coast. It was sort of like Macy’s. It had a floor for everything. It had a floor for S&M, and a floor where they danced and a floor where you can buy sex toys and the works.

And I met Sam Byers, a charming, incredibly sweet guy.

I don’t remember which floor I met him on. One of the more innocuous ones, I think. And we immediately liked each other. I fell madly in love with him. I met his roommate, and then the movie was over and I came back to New York and Virgil Thompson had gotten me an apartment in the Chelsea Hotel. I asked Sam to come, and he came by train with trunks. He had a wonderful style. We lived in 1016, which was at the top, when you get off the elevator on the 10th floor. It was also directly above Virgil’s bedroom. His apartment was downstairs, 920, and he had six rooms. My first year in the Chelsea Hotel, with Sam, was in that apartment. We lived there together for seventeen years.

I introduced Sam to Virgil, down in the El Quixote restaurant. I remember Virgil turning to Sam and pointing to me and saying, “He doesn’t have a good track record; you’d better make yourself indispensable if you want to stick around.”

And Sam did. He did just that. It was really his doing that made the difference. Otherwise, I would have gone through that same routine of being bored in four weeks and wanting to move on. He literally created a life here at the Chelsea Hotel, a wonderful domestic life. When I would do concerts at the recital hall at Carnegie Hall, he’d produce those. He was in advertising. He became a major part of my support. My income would fluctuate enormously. He would support me regardless of whether I had money or not.

He was a major difference. That definitely changed. It had to do with my career. It became so enmeshed, and my career and our relationship with Virgil Thompson which was big. He would come for dinner at least once a week and other friends of ours.

I loved him, it was really a loving relationship, a marvelous one. It was extraordinary.

I was a notorious Don Juan character. The excitement of meeting somebody as a gay man was all about sex , about conquest. That would reach an apex within two or three weeks and then would be done. I would pretend maybe that it was [inaudible 01:03:31] but it was really over. I had innumerable relationships like that. Sam was a major difference.

Chapter 8: AIDS

In 1981 people were starting to get sick. They called it the “gay cancer.” It would progress very rapidly. So you would see, in a matter of two or three months, some close friend shrivel up and die. It was very surreal, this period of denial and strangeness and obfuscation with nobody knowing what was going on. There was that deep-seated fear that we were paying for all of our sins we had committed in the ’60s, all that crazy living and taking such wild chances and so forth.

Craig Lucas’s partner was a doctor who specialized in HIV. So we went to him. And Sam and I both were diagnosed positive. We were frightened and then again in denial and retreat because we didn’t feel sick and we weren’t showing any signs of deterioration. But it was terrifying because it looked then like everybody who was infected was going to die. And indeed, I would say most of them did. At least 75 percent of the people I knew who had AIDS died.

They started having medicines — AZT was one of the first. So Sam and I both started taking medicines, and then he started showing symptoms of deterioration: he contracted Cryptococcal Meningitis, which is one of the many things which you are sensitive to when your immune system is down. And nobody has any idea how he got it. There was speculation — we had an air conditioner where pigeons used to come. And somebody said, “Oh it must have been the pigeon shit being blown into the room.” Nobody had any idea. He started deteriorating rapidly. This was in the early ’90s. He just went on with his life as much as he could. He kept going to his office and he was slowly losing his mind. It was a dilemma for his partners — how to send him home? But Sam treated it with equilibrium. I just couldn’t bear it. It was ghastly. And my cat, Big Gray Puss, this wonderful Maine Coon cat, died at the same time. He was eighteen years old — he and Sam started to deteriorate at the same rate and at the same time. Everything was happening to Sam and to the cat. The cat died, and Sam had barely a mind left — I just went kind of crazy. I couldn’t do anything. Sam took the cat and took it over to the vet to have it cremated. I couldn’t even have picked up the cat and throw it in the garbage can. I couldn’t do anything. But he did, Sam kept that kind of calmness. And then one day, he started having seizures. Sam had developed cryptococcal meningitis, he was losing his mind, wasting away.

He was on intravenous drugs six hours a day, God knows what it was. It’s that last gasp kind of thing, they give you all these medicines and say, “Well, you are going to die.” And I had to give him shots in the stomach and things like that — it was outrageous. And I was just crazy. That was the time that an old friend called me and invited me over, and I knew it was a sexual thing and I was — Oh yes, let me out of here! But it was my introduction to cocaine. To crack. The effect was instantly ecstatic, an enormous relief from that strain I was going through with Sam. It was like nirvana: I was relieved, I could forget about it, I was anesthetized and I was euphoric.

Sam continued having seizures. To witness that was the most traumatic thing for me — somebody you love suddenly becoming this zombie — it’s outrageous. He was taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital and stayed there until he died, on the twelfth floor of St. Vincent’s — it was quarantined because they weren’t sure how the disease was spread, and they weren’t taking any chances. Anybody who came there with full-fledged AIDS was quarantined and separated on this floor. He died December 14th, 1993. Two days before my birthday.

And I became a crack addict.

-